EDITORIAL: Artificial intelligence (AI) was once primarily associated with fun filters, profile picture generators, and creative artwork. Today, it is quietly entering a different space: online disputes, refund claims, and product listings where a single image can influence money, reputation, and trust.

Why it Matters: AI image tools are improving at a speed that outpaces public awareness. What looked obviously fake two years ago can now pass as believable with minimal effort. This shift creates a subtle but growing risk in online marketplaces, especially in refund disputes, warranty claims, second-hand sales, and even service complaints. A convincing manipulated photo can lead to financial loss for sellers, unfair denial for buyers, or simply wasted time arguing over authenticity. The bigger concern is not that if it exists, but that verification habits have not evolved at the same pace. Many people still rely purely on instinct or “it looks real to me,” which is no longer a reliable standard.

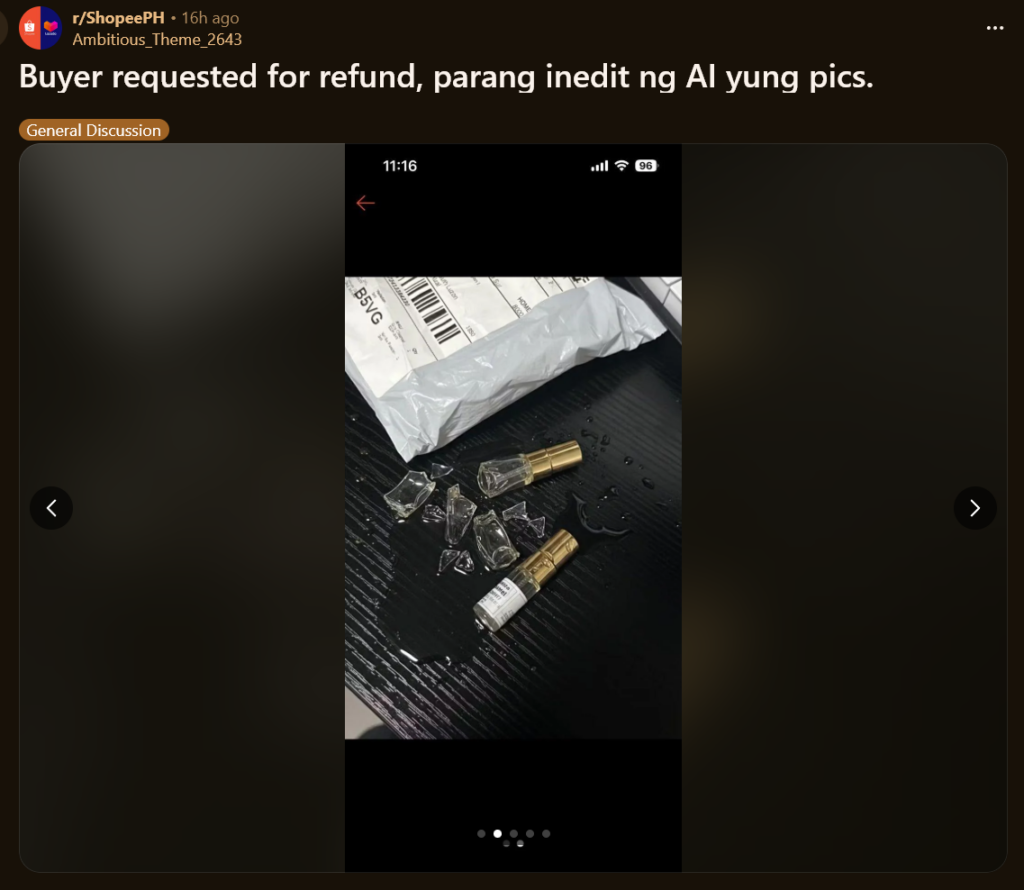

A recent discussion on Reddit’s ShopeePH community highlighted how a Shopee merchant questioned a buyer’s submitted “proof” photo because it appeared to be edited or possibly artificially generated. What stood out was not just the suspicion itself, but how divided the replies were. Some users believed the image was fake, others argued it looked real, and a few suggested using AI watermark detection. The exchange reflects a new reality: many people no longer fully trust images at face value, yet most also do not know how to properly verify them.

The first line of defense is still visual inspection, but it must be done with intention rather than a quick glance. AI images often fail in small details rather than big ones. Text in the background may look almost correct but contain subtle spelling errors or warped letters. Hands and fingers, while much improved in modern generators, can still appear slightly distorted or positioned unnaturally.

Jewelry and accessories such as earrings or glasses may not perfectly match from left to right. Reflections in mirrors, windows, or shiny surfaces sometimes show inconsistencies that do not align with the main subject. Shadows may fall in directions that contradict the visible light source. Skin texture can also appear unusually smooth, almost airbrushed to the point of looking plastic. None of these signs alone confirm AI use, but the presence of several at once should encourage a second look rather than immediate acceptance.

The second layer involves checking metadata, also known as EXIF data. When a genuine photo is taken from a camera or smartphone, the file often contains technical information such as device model, lens type, date and time, exposure settings, and sometimes even GPS coordinates.

This data can be viewed through file properties or online EXIF viewers. Artificially-generated images or heavily edited files may instead show software names or may lack camera information entirely. However, metadata is not foolproof evidence. Social media uploads, screenshots, and messaging apps frequently strip or compress this data, meaning a missing camera tag does not automatically equal AI generation. Likewise, metadata itself can be altered with the right tools. It should be treated as supporting context, not definitive proof.

A third option is the use of image detection services. Platforms such as WasItAI and Hive Moderation allow users to upload an image and receive a probability score indicating whether it is likely synthetic. These systems analyze statistical patterns, compression artifacts, and pixel structures commonly associated with AI generation.

The keyword here is “probability.” These tools do not issue legal-level verdicts. A genuine photo that has been heavily edited can be flagged as AI, while a well-processed AI image might slip through undetected. Running an image through more than one scanner can provide broader perspective, but disagreements between tools are common and should not be surprising.

Another area often mentioned is invisible watermark technology. Google DeepMind introduced a system called SynthID, which embeds hidden digital markers inside images created by certain tools. These watermarks are not visible to the human eye and require compatible detection software to read. In theory, this helps identify whether an image originated from supported platforms. In practice, there are limitations.

Not all generators use SynthID or any watermark at all, and aggressive editing, resizing, or cropping can weaken or destroy the hidden signal. It is also important to note that ordinary users do not always have direct access to official detection systems, making this method more situational than universal.

For online sellers, especially those handling frequent returns or disputes, prevention can be more effective than post-analysis. Requesting real-time verification photos or short videos that show the product alongside a handwritten date or order number can significantly reduce manipulation risk. Encouraging multiple angle shots instead of a single image also makes fabrication harder. Buyers, on the other hand, can protect themselves by comparing listing photos with user review images, looking for consistency across lighting and backgrounds, and being cautious with visuals that appear overly polished compared to the rest of the seller’s catalog. Patterns often reveal more than isolated pictures.

One critical point that often gets overlooked is that there is no global registry of AI images. No master database automatically confirms whether a photo is synthetic. Different AI systems follow different policies. Some embed invisible watermarks, some do not. Some platforms label generated content, others leave it to user discretion. Once an image is downloaded, re-uploaded, cropped, or filtered, many original markers can be lost. This fragmented ecosystem is why verification relies on layered judgment rather than a single technical switch.

Cases like these also expose a recurring concern among online merchants: Shopee’s dispute and refund mechanisms are often perceived as leaning heavily toward buyer protection, sometimes at the expense of sellers who must absorb losses when evidence is unclear or easily manipulated. When a customer submits edited or questionable images as “proof,” the burden frequently falls on the seller to disprove the claim within tight response windows and limited appeal channels.

This imbalance can create situations where fraudulent or deceitful practices slip through, not necessarily because the platform intends to enable them, but because verification tools and review processes may struggle to keep pace with increasingly sophisticated digital manipulation. For small sellers in particular, a single disputed order can translate into lost revenue, damaged ratings, and reduced visibility, reinforcing the sentiment that platform safeguards do not always offer equal protection against bad-faith customer behavior.

AI itself is not inherently deceptive. It is a tool, and like any tool, its impact depends on how it is used. The real issue emerges when synthetic visuals are presented as evidence or reality without disclosure. The practical response is not panic or blanket distrust of every photo, but the adoption of a more deliberate verification mindset. Visual clues, metadata checks, detection tools, and contextual awareness work best when combined rather than used in isolation.

In most situations, the goal is not to prove with absolute certainty that an image is AI-generated, but to assess whether there is enough doubt to pause, ask for more proof, or avoid a risky decision altogether. When images can be created as easily as text, the more relevant question is no longer “Is this real?” but “What steps did I take before believing it?”

Discover more from WalasTech

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Get the latest from WALASTECH directly on your Google feed.

Add as a preferred source on Google

Leave a Reply